Child Development as Foundation for Learning

Growing Up and Down, In and Out

Standing in Space, Growing in relationship

Across the world, in all different continents and cultures, most children learn to walk within their first year and a half of life, and each child, with the right nurturing environment, will manage that amazing achievement, seemingly effortless. What does that early development look like and how can we support it?

How do we all take hold of our body? How do we manage to fully inhabit it, and therefore have it at our calling as a well-tuned instrument? How do we develop the faculties, skills, or abilities of doing: manipulating the world through movement and digestion, of feeling and relating to the world, and of thinking, becoming aware of ourselves, the world and the others in it?

In this article, I will be looking at the development of the child in the first 7 years and how that builds the capacities for academic learning and clear thinking, our social and emotional and movement skills. We will look at the neurological development, motor development and how the child grows towards an independent self in its environment.

At the end, I will try and describe the difference between allowing and supporting development, and teaching. Development happens from the inside out and bottom up, while teaching often comes from the outside and from the top down. I will finish with the question of how these two can work together.

As always the theory is one thing, what I describe here are pictures of a typical development. We are all variations on that theme, we all have managed the ‘typical’ in our own way and we all also have areas that didn’t develop to the ideal. More or less, we all manage with some level of coping mechanisms. Like we can all imagine the ’typical’ or ‘archetypal’ beech tree, depending on the soil, wind, rain etc. each tree is a variation on that theme, every tree looks slightly different. So are we, and is every child we meet, a variation on the theme of ‘human being’, and have we managed a variation of that typical development.

Developing Up and Down:

Development always follows a set order. The timing is very individual, but the order of the different steps or milestones always follows a certain pattern, with each step becoming part of the foundation for the next step to build on.

Growing Down:

Developing control over the body, coming from the horizontal into the vertical position, lifting oneself up out of gravity, happens from top to bottom.

When the baby is born, all movements are uncontrolled and reflexive. Movement of the head sideways or from front to back etc. will trigger movements in the limbs, muscletone changes so that arms and legs stretch out or bend.

We slowly take hold of, and manage to control the body from the head down to the feet.

First the child can lift and turn their head, then the shoulders can be lifted and the arms moved underneath, then the back can be held, the hips when he can sit. The knees can slowly be pushed under the hips and we come to crawling, and finally we have control over the whole legs and feet when we can pull ourselves up and stand upright, then walk.

“The Well Balanced Child” Sally Goddard Blythe, Hawthorn Press, 2005

In order to make all these important steps the child needs lots of floor time, time to strengthen the muscles and bones to allow him to come to that control out of his own efforts and in his own time. For this he needs to have regular time to lie in the horizontal position, both on his tummy and back, with free ability to move head, arms and legs, not restrained by seats or propped up into semi sitting positions.

A supportive environment for this development to happen is very important. That also means not try to hurry a child into sitting or standing before their structural body of bones and muscles is ready, strong enough to do that out of its own accord.

If for example, the muscles in the neck to support the head don’t develop enough strength, the child will still get to walking, but very likely the primitive reflexes will not integrate, and will continue to influence all movements in the limbs, as well as affect the spatial orientation and body geography of the child, and so the free control of the body.

With lots of repetition and movement the nervous system matures and gains full control over all those muscles and bones. Movement is the only way that the brain is going to build and strengthen those neural connections. Movement in a warm, loving and safe environment, where there is real enthusiasm and interest in the child.

That development of inhabiting the body continues beyond the first year and learning to walk, for example at 2 years, a child can walk down stairs but one step at a time, a 3 year old can do that with one foot on each step. By 3 a child can also kick a ball without falling over, so have strong enough balance to move the body freely. By 6 this balance is such that the child can stand on each leg for 15 secs without falling or wobbling.

The result of this development is a free still head on a freely moving body.

Growing Down and from the Inside Out:

The core strength in our torso, shoulders and hips that we so develop, is the foundation for fine motor skills. Strong muscles help to stabilise the body while the limbs move and hands and fingers manipulate objects, write and draw. Being able to hold our head still with strong neck and shoulder muscles, supports the fine muscles in our eyes so that they can work together fluently.

A good muscle tone, the right balance between relaxation and tension in each of our muscles, is important in holding the core still, and to make the fine motor skills accurate.

If muscle tone is low, and the child is floppy, he finds it hard to sit still and upright all day in school, it is hard for him to concentrate on the work, and do fine motor tasks like writing, all day long.

“A Moving Child is a Learning Child”, Gill Connell and Cheryl McCarthy, Free Spirit Publishing, 2014

Growing Up:

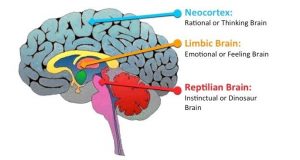

Looking at the maturation of the nervous system that goes hand in hand with the maturation of the movement system, we can see a gradual maturation of the three parts of the brain:

- The reptilian brain, or lower brain, consisting of brainstem and cerebellum. This is evolutionary the oldest part of our brain, and the part that developmentally matures earliest. All the automatic functions of the body are regulated from here, as well as automatic movement patterns. All sense impressions, except smell, also enter the body here.

- The mammalian or limbic brain, where emotions are regulated. Here is also what is called the ‘gatekeeper’ where some of the myriad of sense impressions are let through to the cortex and others are not.

- The human brain or cortex, is where the control over movement, the awareness of sense impressions, rational thinking etc. are controlled. This matures last, with the prefrontal cortex, where complex assessments and judgements are made, only maturing around 23 yrs. of age.

As to the early neurological development that supports learning, Sally Goddard Blythe, a British neuro-psychologist and expert on child development, sums it up beautifully in this little diagram:

- 0-3 yrs.: Primitive reflexes integrate; postural reflexes mature: gradual overriding of the cortex over the reptilian brain. Proprioceptive awareness develops.

- 4-5 yrs.: right and left hemisphere develops symmetrical, with the right slightly more connections to the body than the left, until ± 7 yrs.

- 6-7 yrs.: the corpus callosum (connecting the two hemispheres of the brain) matures, balance mechanism and regulation of fine motor control matures.

“The executive functions of both sides of the brain are built upon firm foundations of sensory motor integration and play, which are primed in the first 3.5 years of life, developed between 4 and 7 years of age through physical interaction and play, and which go through an important stage of neurological reorganisation between 6.5 and 7.5 years of age.”

“The right hemisphere has connections to physical functions like motor control, sensory processing, emotion and emotional memories. The left hemisphere develops centres for auditory discrimination and processing, decoding words, spelling, speech, verbal language, phonetic decoding, timing and aspects of numeracy.

Reading centres of the left hemisphere connect to the right brain between 6.5 and 8 years for girls, and between 7 and 9 years for boys.”

(Sally Goddard Blythe, “Physical Foundations for Learning, Chapter 9, Too Much Too Soon, Richard House (editor) Hawthorn Press, 2011)

Here we can see that the development from the top down in the motor control, goes hand in hand with the neurological maturation of the brain from the bottom up. With this development, the faculties of doing, feeling, thinking develop in this order.

Maturation of a certain part of the brain doesn’t mean that it is not yet available before that time. To mature it needs to build up, develop and grow, so that, when a certain level of skill is achieved, maturation can happen. The seeds need to be available, need to be looked after and supported, tended to, so that at the right time, it can bear fruit and flourish. If we try to bring that fruit too early into reality, before the underlying foundations are ready, we talk about splinter skills. These splinter skills are more like scaffoldings around a house, supporting it, but not part of the foundations on which the house is resting.

At any time in life, the functioning of these different parts can be temporarily lowered when the brain is under stress, to save energy and to make sure survival is guaranteed. Our brain gets put under stress for example through sensory overload, where the brain cannot process the number of stimuli that comes in, or trauma etc. The shutting down happens in reverse order of development: the first faculty to stop functioning fully is the clear thinking: a child in the middle of a tantrum cannot be talked out of it, as the parts of the brain needed to process and organise thinking and speaking are no longer optimally functioning. If the stress doesn’t lower, the next part to shut down is the limbic or emotional brain. Instead we then function out of the primitive part of the brain that holds all our survival mechanisms like the fight, flight and freeze reflex.

Calming that primitive part of the brain, through rhythmic movements like rocking, deep touch, sensory soothing activities etc. will then allow the stress levels to go down and the brain to resume normal functions. If, however, the stress becomes chronic, then a child/adult will mostly relate to his environment from that lower part of the brain, from the fight, flight or freeze reflex.

That means that when we meet children with no learning or academic difficulties, but social difficulties, selective mutism, anxiety etc., working with the development of balance and movement, helping the child to ‘inhabit’ their body better, strengthening and establishing control of the cortex over the reptilian, reflexive brain, allows the strengthening of the foundations on which the functioning of the emotional brain and the cortex are based. Working with developmental processes can re-establish all three parts of the brain and allow their functions to flourish again.

Up and Down – In and Out, in Sense Impressions:

Here I would like to add a picture of the process of taking in sense impressions. Different senses follows different paths of processing, and we are not always fully conscious of all the sense impressions that are going on all the time:

Conscious senses:

Fully conscious: Hearing, seeing

Conscious: smell, taste

Varying degrees of consciousness: warmth, touch

These are sense impressions from the outside, from the world around us to the body, and they come into the brain/nervous system via the reptilian brain (except for smell which goes straight to the cortex), they get filtered and some let through to the cortex in the limbic or emotional brain, and we become aware of them, understand them and form memories of them in the cortex.

Partly conscious senses: balance, movement, proprioception

These sense impressions come from the body and tell us about our body in relationship to the environment. Here the spinal cord, cerebellum and whole brain are involved.

Unconscious senses: life, wellbeing receptors that sense the chemical balance and processes in the body.

These are senses from the body to the body and here the automatic nervous system is involved.

The entire human being is always involved in every sensory experience. For example: I can see or hear things that make me feel sick, or feel rejuvenated, or feeling butterflies in our stomach when we see someone shows metabolic processes happening with sense impressions.

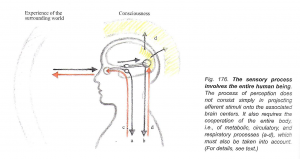

The following diagram shows how the different parts of the brain and body are involved in processing sense impressions, with the example of the conscious sense of vision:

The black line down (a) shows the unconscious part of the perception. For example, when I look at a tree with all its branches, leaves, colours etc., I become aware of some parts of it, but a lot that also enters my eyes stays unconscious: that is filtered out.

The black line down (b) shows the storage of the abstracted image after it has reached the cortex, storing the memory.

The red line (d) shows the retrieving of this image, which is ‘re-enlivened’, ‘re-membered’, by secondary and tertiary cortex fields.

The red line (c) shows how we ‘project’ the impressions back out into the world: We experience the world around us, not as impressions inside, but as spatial realities outside in the world.

J.W. Rohen, Functional Morphology, the Dynamic Wholeness of the Human Organism, Adonis Science Books, 2007, p 250

Sensory experiences can bring up strong memories and also strong physical bodily reactions. This becomes clear when we look at the studies around trauma, and how reactions to traumatic experiences are bodily, metabolic, reactions and experiences. Work by Peter Levin and Bruce Perry shows that it is the body that remembers. Not only traumatic experiences are remembered in our body, but all sense impressions.

The anatomist J.W. Rohen said in the above quoted book:

“Neural processes are complimented by circulatory and metabolic processes, which are as essential to perception as sensory cells and neural circuits.”

Sensory impressions and the act of perceiving, work in both directions: What I see has an effect down to a cellular level in my body and the chemical effects of my metabolism which circulates my whole body via the blood. When these chemical effects reach into the sense organs, that influences my ability to perceive the world around me and my own body. All senses are working together at all times.

This makes it all the more important that we are careful and conscious of the environment a child grows up in, both at home and in the classroom. What is the quality of what they see, hear, feel, smell, taste etc.?

Also the quantity of the sense impressions is important. We not only take all of that into our bodies, but we also must be able to “lift it back up” and “give it back out” so to speak. If we are overwhelmed by all that comes in, it is hard to digest all these impressions and lift them up into consciousness and memories and express them via our thoughts and speech.

Developing In and Out:

As the understanding of the sense impressions and the effect of our environment shows, we are never totally separate from our environment, there is always an influence.

That influence is ‘total’ at birth. Then the baby and his environment are as 1. The baby is one big sense organ, with no ability for selection or filtering yet developed. It is like a drop in the ocean: that drop cannot decide not to be salty. What is around is within through osmosis.

Only gradually does the child develop the ability to separate himself out, becomes a separate point in the wider periphery:

- -At birth: baby and environment are one, baby IS one Sense Organ

- -First smile: first recognition of other

- -2 y: “NO” first setting off against other

- -3 y: “I” first naming of Self

- -4 y: start expressing own voice

- -6 y: start creating own imaginative stories, balance

- -9, 10 y: more conscious of other’s differences

- -12 y: puberty, challenging the rules

- -16 – 18 y: young adult, starting to look for own path

- -21 – 23 y: Self-knowledge, own judgement, separate “I” in world

For example, for the little baby, mum’s mood is the baby’s mood. He cannot yet protect himself from that. Around 5, 6 year, the child becomes a bit more aware that other people are sad or happy, by 9, 10 that knowing becomes a bit clearer and they can start to name the differences they notice in other people, but it’s still hard not to be influenced by the mood of the teacher or the children in the classroom.

This makes it not only important what the quality and quantity of the child’s sense impressions are, but also who and how we as adults around the children are. What do we think, feel, do, how do we hold ourselves and be the example that they can ‘absorb’? How we can hold ourselves, as parents, teachers, therapists etc., how we develop and become self-aware, are willing to keep learning and changing, will have an immediate effect on how the children in our care can be and become.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In and Out, Up and Down.

Here below are some examples of where we can see these different patterns of development:

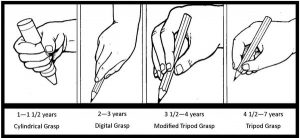

- The Pencilgrip: From gross motor to fine motor, from in to out, from the centre to the periphery:

1) the whole arm moves, shoulder is stable

2) the upper arm is now also stable, movement from elbow down

3) the whole wrist is moving, arm stable

4) the wrist is stable, only 3 fingers moving, pencil an extension of index finger

- In language development: From ‘top down’:

± 2 y :

Nouns: Naming Phase: ‘chair’: Nerve-sense: Thinking

2nd y :

Adjectives: 2 word sentences: ‘big chair’: Rhythmic: Emotional

± 3y :

Verbs: Talking Phase: ‘sit big chair’: Metabolic: Doing

AND becoming an individual aware of and able to share inner world, from periphery coming in, from out to in:

- Why? What? Who? Questions, first expression of inner thinking triggered by outer impressions: ± 3 y

- Rhythm, Musicality, Repetition of stories, songs, playing in parallel with other children, finding own voice: 3 – 4 – 5 y

- Expression of own imaginations, telling story out of own inner pictures: 6 – 7 y

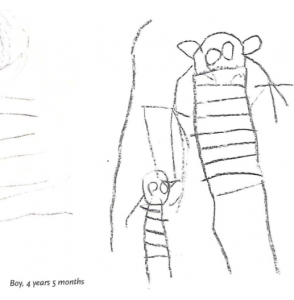

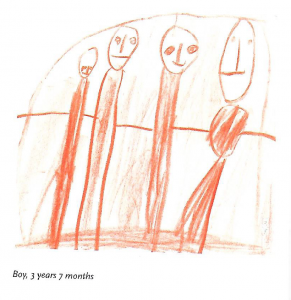

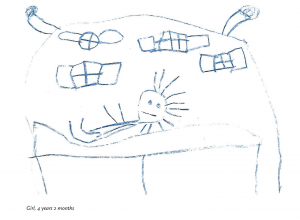

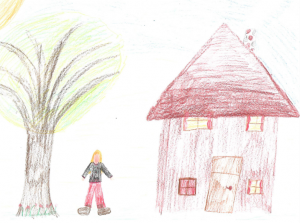

- Drawing of people:

From the top down:

1) head

2) head and Trunk/Limbs

3) Head, Torso, down to feet (at the time that balance is also becoming more secure) (boy, 5 y, 6 m)

Michaela Strauss, “Understanding Children’s Drawings”.

- Drawing of the house:

Separating out from the environment:

1) People encircled by the house

2) Inside and Outside view of house simultaneously

Michaela Strauss, “Understanding Children’s Drawings”.

3) Seeing the whole house from the outside

(girl 9 y)

Development and Teaching:

Development happens from the inside out. The Self of the child is the motivator and initiator of development. For that to be successful, he needs to be surrounded by an environment and people that are supportive and worthy of absorption through ‘osmosis’, worthy of imitation.

Although I have looked mainly at the development in the first 7 years of life, that is not when it ends. In early childhood education, we are to a big degree open to the idea that children are still developing and that we need to support this. When children start school, it seems that an unconscious attitude appears that it is now time to learn, as if development has no longer any part in growing up. Development continues all through our lives, we keep growing, learning, changing etc., we keep developing as human beings. We can keep striving to become better at it, at being human.

Development is ‘nature’ that needs ‘nurture’ to be able to come fruition. Human development needs the social context, needs human relationships to happen. Nurture can be very supportive so that development can unfold as it is meant to do. Nurture can also fall short, or as we saw, trauma or overstimulation of the senses, can hinder development, stall it, or even reverse it.

When this happens, we can though create the right environment so that development can come back on track and catch up to what may have seemed lost.

When nurture can be in harmony with the inner nature of development, then teaching and child development can go hand in hand and we can follow the developmental way of learning. Integrating what is learned and achieved through development, happens not only via our thinking and intellect, but, as we saw in our triune brain development, we need to be able to move it, do it, make an emotional connection and deeper understanding with it, repeat it many times, and then we can analyse it, take it apart and bring it into our consciousness: from the bottom up: first doing, feeling and then thinking.

For example: when we ‘teach’ grammar in school, we need to understand that grammar has developed naturally with the linguistic development in the early years. This linguistic development of grammar is the same in every child, in any language, even sign language. Teaching grammar is about intellectually understanding that, which has naturally come about within the social interactions of the child with the adults around him.

If teaching is not in tune with where the child is at in his development, then he may not be able to take on what is brought to him from the outside. Repeating the things he is struggling with may not have any impact, and doing more of what is not working, will soon erode self-confidence. Approaching difficulties with learning only via the intellect does not always reach the underlying reasons of why learning may not be easy.

When we can bring development and teaching in tune with each other, then growing up can seem like that effortless and joyful process.

Conclusion:

Reaching all the milestones in child development, becoming a “self” and separating out from the world, is not a linear process. We grow up, we grow down, we grow in and we grow out. And all these different paths of development happen at the same time and influence each other. It is a complex process, and yet it can all happen seemingly effortlessly when all goes well.

The modern world though is less and less supportive of normal development. A lot of unforeseen circumstances can put a blockage in its way, like complications at birth, hereditary factors, accidents that can happen to all of us etc. But apart from the unforeseen circumstances, our modern world is often overloaded with sensory impressions, we have become impatient with allowing children to take their own time with their developmental processes, and we are often overbearing with trying to ‘teach’ developmental steps, which cannot be taught.

We seem to have lost the instinctive knowledge of what it means to provide that supportive environment for development. It is now something we need to regain consciously, so that we again can support the children in our families and classrooms.

Development happens within the social context of human relationships. In relationship, we “breathe” in and out between self and the other, in sense impressions we “breathe” in and out between self and the world, etc.

In his book “Seeing Voices” (p 151) Oliver Sacks quotes L.S.Vygotsky (1896-1934) who ‘saw the development of language and mental powers as neither learned, in the ordinary way, nor emerging epigenetically, but as being social and mediate in nature, as arising from the interaction of adult and child.’

The more secure we are in our “point”, through a healthy up-down motor-nervous development, inhabiting our body as well as we can, the easier it is to do the interacting, the breathing in and out without losing ourselves in the other or the environment, the easier it is to build healthy social relationships.

The more secure we are in our “point”, the better our relationship to space and time is. Left and right, only make sense when there is a central still point from which we can move to the left, right, above, below, in front and behind. Spatial orientation depends on an innate knowing of where our own body is.

A secure point allows me also to sequence in time and orientate in the past, present and future.

Supporting children in their developmental process can help them to become more secure in their own Self, inhabit their body in a healthier way, so that they, with the skills of doing, feeling and thinking, can meet the world in their own individual way, with their own individual gifts. And are free to give their unique gifts to the world, become their own variation on the theme of ‘being human’ with a strong self-confidence and self-esteem.

Differences are to be celebrated!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Appendix:

- Academic skills of Reading and Writing and Maths require:

- Recognising form

- Spatial orientation: left/right, above/below

- Still head, with free limb movements

- Ability to sit still: balance, core strength

- Fine motor skills: eyes working together, pencil grip

- Auditory and visually Processing skills

- Memory

- Experience of the whole, before it can be divided in parts

2. Areas of learning that can be enhanced by addressing underlying developmental difficulties:

- Literacy and numeracy: performing below age level academically, skips lines when reading, confuses signs in maths, reversals in writing, reading, difficulty with sequencing.

- Motivation: easily distracted, short attention span, difficulty learning new tasks, difficulty completing school work, in school and at home.

- Concentration and Memory: difficulty remembering or following instructions, appears not to listen, needs things repeated, disorganised, loses things.

- Sense of Self: anxiety, over emotional, hypersensitive, mood swings, low self-esteem, difficulty with sensory processing.

- Behaviour and Social skills: difficulty with relationships, easily frustrated or blames others, anger attacks or outbursts, behavioural problems at school or at home, meeting the world with opposition.

- Handwriting skills: awkward pencil grip, poor handwriting, avoids writing tasks.

- Coordination and balance: clumsy or accident prone, poor balance, lack of coordination, low muscle tone, prone to car sickness, mixed dominance, retained primitive reflexes, finds gross and/or fine motor activities challenging.

- Spatial Awareness: difficulties with left, right, above, below, in front and behind.

Bibliography:

Connel G. and McCarthy C., “A Moving Child is a Learning Child, How the Body Teaches the Brain to Think”, Free Spirit Publishing, 2014

Goddard Blythe S., “The Well Balanced Child, Movement and Early Learning”, Hawthorn Press, 2005

Hannaford C., “Smart Moves, Why Learning is not all in your Head”, Great River Books, 2005

House R. Editor, “Too Much, Too Soon, Early Learning and the Erosion of Childhood”, Hawthorn Press, 2011

Konig K., “The First Three Years of the Child, Walking, Speaking, Thinking”, Floris Books, 2005

Levine S. K., Trauma, Tragedy, Therapy, The Arts and Human Suffering”, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2009

Perry B. and Szalavitz M., “The Boy who was Raised as a Dog, and Other Stories from a Child Psychiatrist’s Notebook”, Basic Books, 2006

Rohen J. W., “Functional Morphology, The Dynamic Wholeness of the Human Organism”, Adonis Press, 2007

Sacks O., “Seeing Voices” Picador, 2012

Strauss M., “Understanding Children’s Drawings, Tracing the Path of Incarnation”, Rudolf Steiner Press, 2007